59811

Many thanks to Lostin, Alessandro, Brian, Brady, and Daniel Cumming for reviewing earlier versions of this article. actionable insights

introduceThe Solana Virtual Machine (SVM) is one of the most misunderstood systems in blockchain today. Unlike the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM), which explicitly refers to an opcode executor, the term SVM covers the entire transaction execution pipeline, from the Banking Stage scheduler to the sBPF bytecode interpreter itself. This ambiguity reflects Solana's architectural differences: there is no traditional specification that defines "SVM" in isolation. The only close specification relates to the Solana Virtual Machine Instruction Set Architecture (SVM ISA), which describes how sBPF bytecode must execute, but does not describe the broader runtime. This article is intended to be a comprehensive reference on what SVM is, how it works, and why it is fundamentally different from the perspective of Anza's Agave validator implementation. An exploration of how Firedancer clients operate, and their custom virtual machine implementations that conform to the SVM ISA, is beyond the scope of this article. We are interested in examining the actual code base, not some abstract specification. We traced the complete execution pipeline—how Rust source code is compiled into sBPF bytecode via LLVM, how the program is deployed and verified, how the runtime configures an isolated execution environment for parallel execution, and how transactions interact with the deployed bytecode. The previous sections contextualized the fuzziness of SVM and provided an overview of how it works. The remainder of this article is intended for a more technical audience seeking a rigorous understanding of Solana's execution layers. a controversial definition“The term "Solana Virtual Machine" (SVM) has sparked heated debate within the community, especially in the wake of network expansion and the emergence of other layer blockchains built on top of Solana. The debate arises from the scope of the term: is SVM strictly a low-level sBPF interpreter, or does it contain the full transaction execution stack? A narrow view views SVM as an opcode executor similar to a traditional virtual machine (VM), such as the EVM. More specifically, it is an eBPF-derived virtual machine (rBPF, now sBPF) that interprets and JIT compiles bytecode. This view emphasizes that the SVM is a sandboxed, register-based executor that processes instructions such as ALU operations or Solana-specific system calls. Essentially, SVM is inspired by the Linux eBPF security model, but is customized for blockchain infrastructure. This is consistent with phrases like SVM ISA (Instruction Set Architecture) in the verifier code, where SVM is just the VM layer. A broad view defines SVM as the entire transaction execution layer of the Solana validator. This includes not only running bytecode, but also upstream components such as the Banking Stage's scheduler, compute unit budgets, and status updates via the Accounts Database (often called AccountsDB). It is the "runtime" that converts raw transactions into verified state changes. The reason for the ambiguity is that official Solana communications use "runtime" and "SVM" interchangeably without a clear definition. Anza adds much-needed clarity to this debate, clearly validating it while also promoting a pragmatic, action-oriented, engineering-based perspective. They view SVM as a Bank-driven runtime that provides the eBPF VM, a framework that provides a broader, pipeline-inclusive view that can be used to formulate the correct definition of SVM. This is formalized in Anza’s official SVM specification, which defines SVM as “the component responsible for transaction execution,” packaged into a standalone library for validators, fraud proofs, sidechains, and more. For our purposes, we can define the Solana virtual machine as:

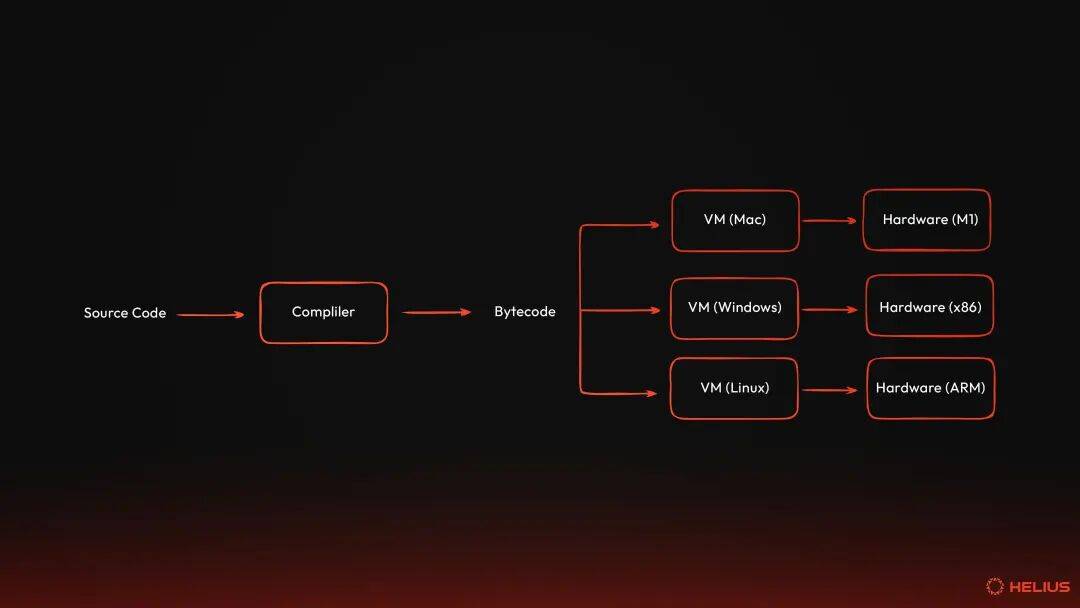

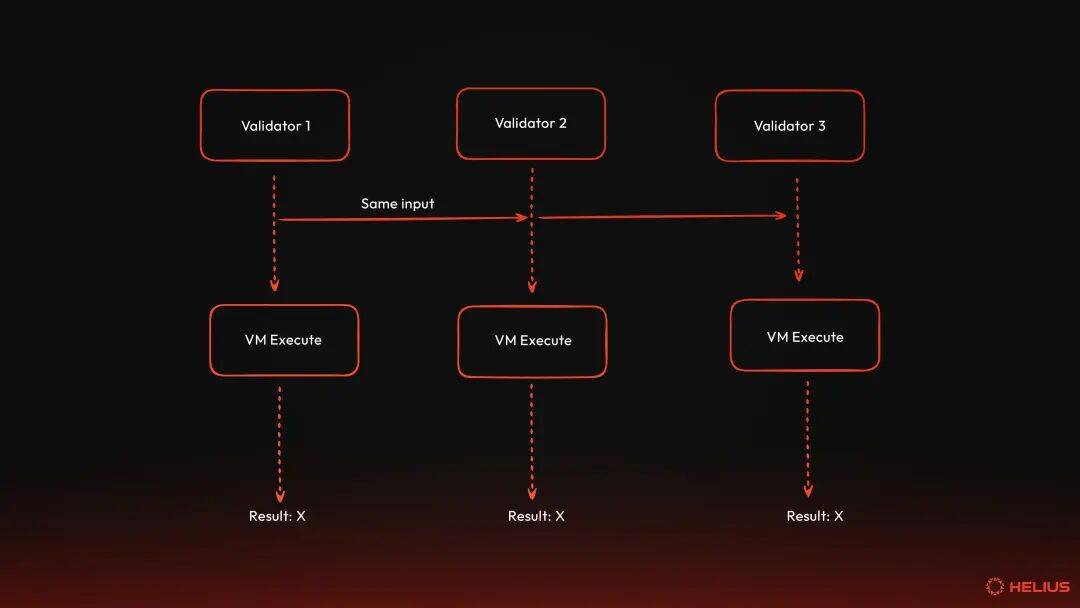

SVM at a glanceThe Solana Virtual Machine (SVM) is used as the execution environment for processing transactions that interact with on-chain programs on the network. It is the runtime layer where code meets state—the execution environment that transforms cryptographically signed transactions into verified state changes. To truly understand SVM, we must first understand what virtual machine means in a blockchain environment. virtual machineA virtual machine (VM) is software that virtualizes or emulates a computer system, providing an isolated execution environment that behaves like physical hardware. The concept originated from IBM's research into mainframe systems in the 1960s, which enabled multiple users to run different operating systems on the same physical machine. Virtual machines are mainly divided into two categories: system virtual machines and process virtual machines. The former provides a replacement for a real machine, while the latter aims to execute programs in a platform-independent environment. For our purposes, we are interested in system virtual machines, we will call them "virtual machines" or simply "VMs".  Virtual machines solve several fundamental problems. First, they provide an abstraction layer to the hardware. In other words, programs written for VM can run on any physical hardware that supports VM without having to rewrite the program. Java's "write once, run anywhere" philosophy is exemplified by the fact that Java bytecode runs the same way on Windows, macOS, Linux, and other systems with the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) installed. Virtual machines also provide isolation and security guarantees. Each VM instance runs in a sandbox, which means that it cannot access the resources of the host system or other VMs unless explicitly allowed. Therefore, if the program crashes or contains malicious code, the damage is limited to that VM instance. This isolation principle is why cloud providers like Google Cloud and AWS use VMs to separate customer workloads. Virtual machines also provide predictable output. This means that the virtual machine provides a controlled environment where the same input always produces the same output, regardless of the underlying hardware. This predictability is critical for debugging, testing, and achieving consensus among distributed systems. Virtual machines can also be very efficient. Modern virtual machines use just-in-time (JIT) compilation to minimize performance overhead. JIT compilation converts VM bytecode into native machine code at runtime to achieve near-native performance while maintaining portability and the security guarantees mentioned above. Virtual machines in the blockchain Blockchain adopts the concept of VMs to solve a unique challenge: How can thousands of independent computers around the world execute untrusted code and achieve the same results? The VM acts as a deterministic runtime environment for executing smart contracts (i.e., programs on Solana) and managing the state of the network (i.e., the current state of all accounts, balances, and other data on the network). When a transaction is submitted to the blockchain, the VM is responsible for:

The specific rules under which state transitions occur are defined by the VM's instruction set architecture and runtime constraints. How SVM worksSVM is a pipeline of subsystems that work together to execute transactions safely and efficiently. Bank coordinates execution for a specific slot, manages account status, executes consensus rules, and coordinates operations between the Banking Stage and the persistent storage (i.e., AccountsDB). Each Bank represents the status of all accounts in a specific slot and goes through three life cycles: active (i.e., open to new transactions), frozen (i.e., not open to new transactions as the slot is completed), and rooted (i.e., part of the canonical chain). The Banking Stage is where transactions are executed in the validator’s Transaction Processing Unit (TPU). It receives verified transactions from the SigVerify stage, buffers them, and schedules them for parallel execution using conflict detection on account locks. Worker threads in the Banking Stage process batches of non-conflicting transactions, calling the Bank's execution method to load accounts, provide an sBPF VM instance for each instruction, execute the program bytecode, and collect the results. The Banking Stage continues to process batches of non-conflicting transactions until the Bank is frozen at the slot boundary. Note that batches are different from entries, which are units of transaction records written to the ledger for replication and consensus. BPF Loaders manages the program lifecycle: deployment, JIT compilation, upgrade and execution. When an instruction targets a given program, an sBPF VM is provided with its own memory region and computational budget, and execution is handed over to the program's bytecode. The sBPF VM is the sandbox execution environment where program bytecode actually runs. It is derived from Linux's eBPF and uses a register-based architecture with 11 general-purpose registers. The VM enforces memory isolation through five distinct memory regions, each with clear boundaries and permissions. The VM also meters compute unit consumption to prevent runaway execution and schedules system calls to perform privileged operations such as cryptography, logging, or cross-program invocations (CPI). AccountsDB is the persistent state layer where all account data resides. Load account state before execution and leverage caching to avoid repeated disk reads for frequently accessed accounts. Upon successful execution, the update will be committed back to AccountsDB. If execution fails, all state changes will be atomically reverted. Together, these components form SVM, a decoupled, reusable execution engine. What’s special about SVM: Pre-declared accountsThe decisive architectural decision of SVM is that all transactions must explicitly declare which accounts they will read from and write to before execution begins. This simple requirement is baked into the transaction format itself, unlocking two transformative features that set Solana apart: parallel execution and localized fee markets. Parallel execution (Sealevel)Unlike the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM), which processes transactions sequentially—one at a time, waiting for each transaction to complete before moving on to the next—SVM scales horizontally by executing multiple transactions simultaneously across multiple CPU cores. This parallelization is possible because all Solana transactions explicitly declare which accounts they will read from and write to before execution begins. Declaring which accounts a transaction will read from and write to allows the runtime to analyze account dependencies to detect conflicts and schedule non-conflicting transactions:

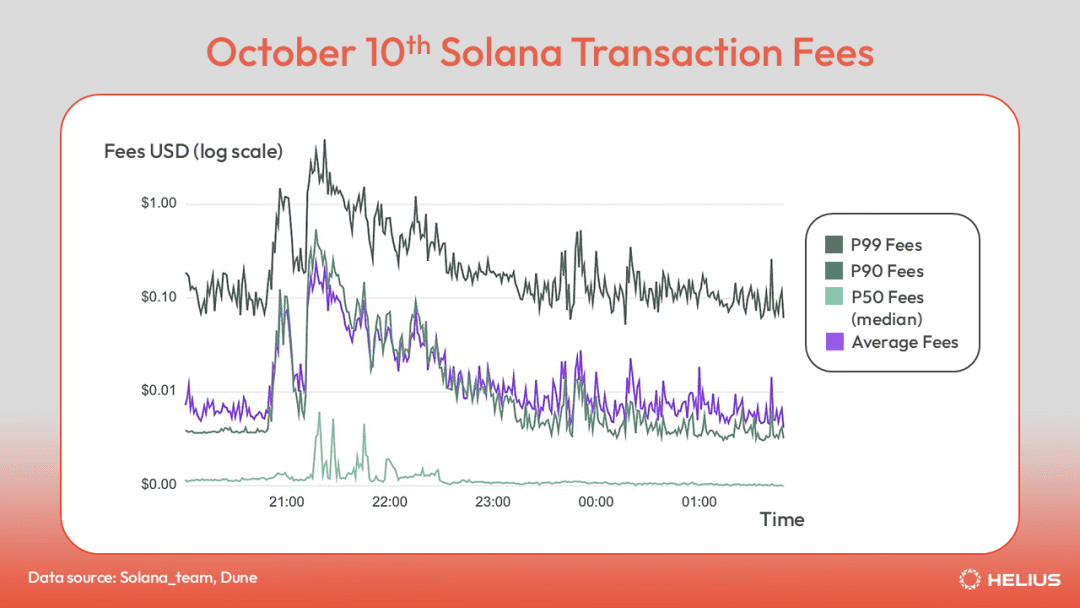

local fee marketBecause the runtime knows exactly which accounts each transaction will access before execution, fees can be localized to specific accounts rather than competing across the entire network. This is a concept called the local fee market. On Ethereum and other EVM chains, every transaction competes in a single global fee market—sending ETH to a friend, minting an NFT, or transacting on Uniswap all bid against each other for the same block space. Surge in one area drives up costs for everyone, regardless of whether they are trying to do something completely different. On Solana, only transactions accessing the same account compete with each other. Users transferring SOL between two accounts do not have to worry about simultaneous minting of popular NFTs. Priority fees for transactions are determined solely by account competition. This localization is why Solana transactions stay cheap even during peak activity periods.  For example, on October 10, the cryptocurrency market experienced its largest liquidation event ever. Despite record levels of activity, Solana transaction fees remain relatively cheap, with the median transaction fee at $0.007, the average fee briefly hitting $0.10, and the top 1% of transactions peaking at just over $1.00. During the same time frame, both Ethereum and Arbitrum’s median fees surged above $100, while Base’s fees peaked at over $3. paradigm shift

SVM represents a fundamentally different approach to blockchain execution. Bitcoin introduced programmable money. Ethereum introduces universal smart contracts and arbitrary on-chain execution. However, both are constrained by sequential execution and global fee markets—architectural decisions that fundamentally limit throughput and cost. SVM breaks away from traditional constraints to provide a network that can handle high throughput without sacrificing programmability or forcing users to participate in exorbitant fee auctions. The decision to pre-declare an account is both simple and powerful because it enables parallel execution on CPU cores and localizes fees to the account-level market. Of course, these are not the only optimizations Solana offers compared to other blockchains. Solana's credo of "increase bandwidth, reduce latency" and obsessive obsession with realizing the dream of Internet capital markets has resulted in a variety of performance optimizations, design choices, and implementations that foster a high-throughput network. The rest of this article explores how exactly this works—how Rust source code is compiled into bytecode, how that bytecode is deployed and verified, and how the runtime provides an isolated execution environment to safely run thousands of programs in parallel while maintaining strict determinism and safety guarantees. From Rust source code to sBPF bytecode: compilation pipelineRust Rust is the universal language in Solana program development. Frameworks like Anchor provide developers with a powerful, opinionated way to efficiently build secure programs. solana_program aims to be the basic library for all on-chain programs. Recently, Pinocchio, a highly optimized, zero-dependency library, has become the first choice for developers looking to build native Solana programs. Regardless of the framework or library used, all programs have an entry point that the runtime will call when the program is called. The entrypoint macro of solana_program emits the standard boilerplate required to initiate program execution. That is, deserialize the input, set the global dispatcher and panic handler. Pinocchio exports entry point macros that function similarly, but decouples the entry point from the heap allocator and panic handler settings, giving developers more optionality. Basic procedural anatomyA program is an account type that can run code. More specifically, the program is an executable account that stores blobs of sBPF bytecode in an account owned by the BPF loader, which has a unique public key. Programs are stateless by design: all persistent data is located in separate accounts, and programs can read or write data from these accounts when called. SVM expects all programs to have a specific skeleton structure - an entry point that accepts three inputs:

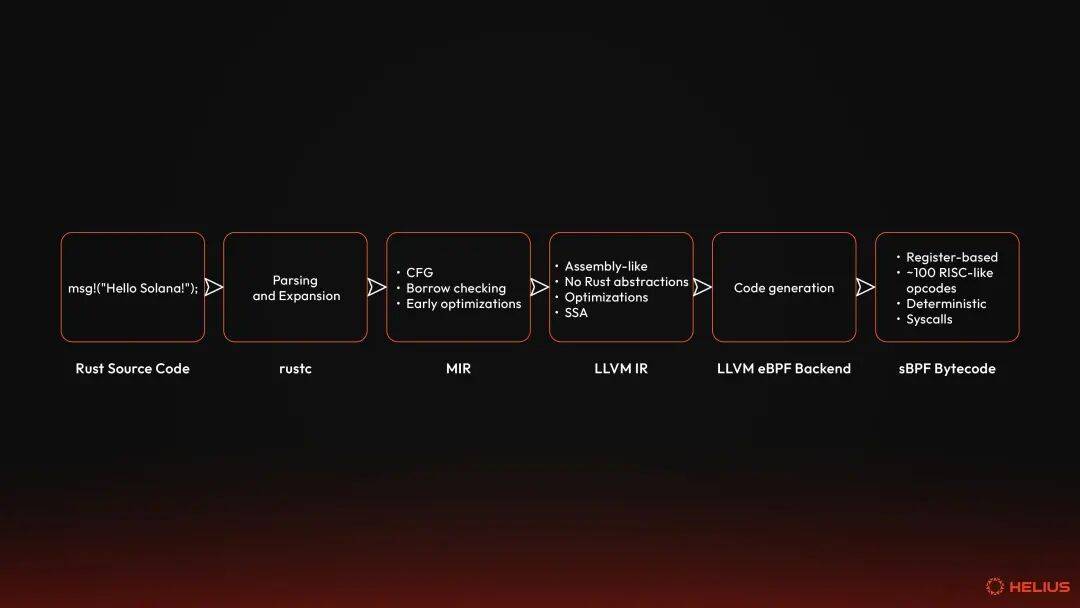

The program should handle these inputs through its entry point, modify the associated writable account, emit logs or events, and then return a success status indicating whether it was able to complete all of these operations successfully. This boils down to a process_instruction function. A simple program written in Rust using the solana_program crate looks like this: simple_rust_program.rs use solana_program::{Under the hood, this is all defined by the SVM's Application Binary Interface (ABI), which we'll explore later. Rust compiler and LLVM IRLike many other programming languages, Rust is a second-order abstraction built on top of assembly. It's designed for people to write safe, concurrent, and readable code without having to micromanage every tiny hardware interaction. However, the computer doesn't speak Rust, nor any high-level language. Computers understand machine code—binary instructions tailored for a specific architecture or virtual machine. All programs are ultimately converted into binary code, and this conversion is ultimately completed by the computer. Compilation is a multi-step transformation process that strips away high-level abstractions, optimizes for efficiency, and outputs executable bytecode. rustc is the official compiler for Rust. Most developers typically don't interact directly with rustc ; They call it through Rust's package manager, Cargo. Nonetheless, rustc takes Rust source code through three main stages before emitting executable bytecode. Each stage strips away abstractions, enforces safety, and prepares code for the next transformation:

parse and expandThe compiler reads the given Rust file (represented by the .rs extension) as plain text. It searches for specific tokens (for example, use, fn, None, impl, &[u8]) in a process called lexical analysis. Lexical tokenization is the process of converting text into meaningful lexical tokens that belong to a given category (eg, identifiers, operators, delimiters, literals, keywords). rustc takes these lexical tokens and converts them into a data structure called an abstract syntax tree (AST). This tree-like structure represents the nested, hierarchical structure of Rust source code. That is, functions contain blocks, blocks contain expressions, expressions contain operators, and so on. Although the abstract syntax tree is still at a high level, it provides a faithful representation of the source code and its underlying logic. After building the abstract syntax tree, the compiler performs several key transformations:

At this stage, the compiler handles unsafe code. Unsafe code allows developers to perform operations that bypass Rust's safety guarantees (e.g., dereferencing raw pointers, calling external functions, implementing unsafe traits). It acts as an intentional escape hatch for low-level control, relaxing certain rules while still requiring code to compile under Rust semantics. This is key for Solana programs, where it may be prudent to use unsafe code to improve the performance of performance-critical operations, such as zero-copy account deserialization (for example, in Pinocchio's account wrapper structure). Unsafe code is first identified in the AST construction after lexical analysis, because unsafe tokens are identified and marked as special nodes. It is then processed after the AST has been expanded during type and borrow checking. The compiler ensures that unsafe operations are restricted to unsafe environments, otherwise it flags an error (e.g., "Cannot dereference raw pointer outside unsafe code"). For example, the compiler does not check whether unsafe code is corrupting or managing memory incorrectly. At the end of this phase, the expanded abstract syntax tree (now a typed high-level intermediate representation) is a verified, reduced representation of the Rust source code. MIRThe typed high-level intermediate representation then drops down to a mid-level intermediate representation (MIR), a Rust-centric form that represents the source code as a simplified control flow graph (CFG). All Rust-specific syntactic sugar and complex constructs (e.g., pattern matching, traits, closures) are represented as basic blocks, including assignments and branching. These basic blocks are connected by jumps (more specifically Gotos) and branches, making it easy to reason about the flow of the program. MIR is not strictly required. The compiler can directly reduce a typed high-level intermediate representation to an LLVM IR. However, MIR provides a Rust-aware layer that allows the compiler to enforce Rust-specific rules and perform optimizations before applying LLVM's general optimizations. This makes MIR well-suited for checks and transformations that are too high-level for LLVM but too low-level for typed high-level intermediate representations, including:

For example, earlier we called msg!("Hello, Solana!") in the sample Rust program. This is a macro defined in the solana-program crate that, for a single expression like a static string, expands during the macro expansion phase to a direct call to sol_log($msg), where $msg is the expression. The sol_log system call obtains a pointer to the string data and its length and logs it to the output of the SVM without incurring formatting overhead. This can be simplified in MIR to: bb0: {here,

MIR's focus on Rust semantics makes it an ideal place to discover inefficiencies and debug expensive patterns in CU. For example, if your logs contain dynamic strings, MIR may identify additional allocations or loops that can be optimized. Developers can use the command cargo rustc -- -Z dump-mir=all to dump MIRs. MIR ensures that the code is semantically sound, optimized, and stripped of all Rust-specific rules before eventually reducing it to LLVM IR. Note that this is often referred to as the code generation phase. This doesn't have to be LLVM. However, LLVM is common and what most people think of when they think of Rust code generation. The Rust compiler also ships with the GCC and Cranelift backends, which emit GIMPLE and CLIF respectively. We focus on LLVM IR in the Solana environment, but note that this is not always the case with Rust in general. LLVM IRLLVM originally meant "low-level virtual machine" and referred to a modular compiler framework. Rather than having a separate compiler, LLVM is a toolkit of reusable components for building compilers, optimizers, and code generators. Many languages (eg, Rust, C, C++, Julia, Swift, Brainfuck, Zig) use LLVM to take advantage of its capabilities on multiple architectures, from x86 CPUs to virtual ISAs. rustc converts MIR into LLVM IR (Low-level Intermediate Representation for Virtual Machines) - the bridge between Rust semantics and the bytecode ultimately deployed on Solana. It is closer to machine code, with explicit memory allocation (i.e. alloca), stores, loads and function calls. It has no concept of ownership, lifetime, or traits, because these Rust abstractions have been expanded and no longer exist—the guarantees of previous rounds are preserved. Various optimizations are applied at this stage, including:

Therefore, LLVM provides us with:

Rust programs are typically compiled for hardware targets such as x86_64 or ARM. However, Solana programs do not run directly on the hardware. Instead, they run inside the Solana virtual machine. Therefore, the LLVM backend reduces the LLVM IR to BPF bytecode, and on Solana it becomes sBPF bytecode (i.e., a fork of eBPF that removes undefined functionality and introduces Solana-specific system calls). Note that while Rust is the general language for Solana program development, any language that can target LLVM's BPF backend can be used (eg, C, Nim, Swift, Zig). eBPFLLVM IR is reduced to eBPF, the register-based ISA that forms the basis of the Solana runtime. eBPF (Extended Berkeley Packet Filter) has its origins in the Berkeley Packet Filter (BPF), which was developed by Steven McCanne and Van Jacobson at Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory in 1992 for Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD) Unix systems. Essentially, BPF is a network tap and packet filter that allows network packets to be captured and filtered at the operating system level without copying the data and leveraging qualifiers. Since then, eBPF has evolved (i.e., been extended) into a general-purpose sandboxed VM in the Linux kernel. It unlocks something similar to what JavaScript unlocks for web development - it's the kernel's secure scripting engine. eBPF enables developers to run small, proven programs directly in the Linux kernel with a constrained instruction set for tasks such as performance monitoring, observability, security, and networking. This is important because developers get: - Sandboxed execution: eBPF programs run in a restricted virtual machine within the kernel, meaning they cannot crash or corrupt kernel memory.

Solana requires a deterministic, secure, and performant VM to run untrusted programs across its entire validator set. eBPF provides a mature security model, a portable and efficient ISA designed to run thousands of lightweight programs, and JIT support for better performance. Therefore, instead of inventing a completely new VM, Solana forked eBPF and created sBPF. sBPF Initially, Solana Labs forked Quentin Monnet's rBPF to create a Solana version of rBPF that ensures that each validator has a bytecode format that produces exactly the same results for a given program and input. It was thought that forking eBPF was needed because Solana's consensus requires deterministic execution and bounded resource usage. While eBPF itself is deterministic, Solana requires additional guarantees and blockchain-specific features:

Notably, it is designed to run in user space rather than the kernel, thus avoiding the need for kernel permissions or modifications. This enables deployment in a variety of operating system environments without requiring root access or custom kernel modules. User space is a practical alternative to Solana - portability, testing, and easier deployment. Despite running in user space, the JIT still achieves near-native performance. Additionally, userspace execution allows testing and fuzzing without kernel access. rBPF is no longer used. Instead, when Anza was created, they forked rBPF to create sBPF (Solana Berkeley Packet Filter). The rBPF GitHub repository owned by Solana Labs was archived on January 10, 2025. SVM ISAThe SVM ISA (Solana Virtual Machine Instruction Set Architecture) is the core specification that defines how Solana-compatible VMs (for example, Agave's sBPF or Firedancer's reimplementation) must execute programs. It is not the VM itself, but a standard or contract that ensures consistency and protocol compliance between various SVM implementations. It is the SVM ISA that imposes these security and deterministic constraints on eBPF, removing kernel-centric features while adding blockchain-specific features. ISA manages registers, instruction encodings, opcodes, classes, validation rules, panic conditions, and the application binary interface (ABI). Any changes to the SVM ISA must be implemented via SIMD to support the controlled evolution of this instruction set, ensuring deterministic execution between validators. registerRegisters are tiny memory slots inside the VM that hold numbers or addresses while instructions are running, similar to variables or labeled boxes on a workbench. The SVM ISA defines a 64-bit register architecture with 11 general-purpose registers (R0-R10) and a hidden program counter. The registers are 64 bits wide and are used for integers and addresses, allowing efficient handling of large values or pointers. R0 holds the function return value, R1-R5 passes the first five function parameters, such as parameters, R6-R9 are saved by the callee and remain unchanged across function calls, and R10 is used as a read-only frame pointer to mark the current stack frame. A hidden program counter tracks execution, indicating which instructions are to be executed next. instructionAn instruction is a single operation that the VM knows how to perform, such as "add these two numbers" or "jump to this line of code." Instructions have a RISC-like design with around 100 opcodes as compared to thousands of opcodes in CISC architectures like x86, making verification fast and JIT compilation efficient. Instructions are encoded as 64-bit values in little-endian format and are structured as follows:

opcode tells what to do, dst_reg tells where to put the result, src_reg tells where the input came from, offset tells which memory offset to look at, and immediate is an extra constant that can be included in the instruction. lddw (or load doubleword) is the only wide instruction that occupies two 64-bit slots to support a full 64-bit immediate value. Instructions are divided into different categories, including memory operations, arithmetic or logical operations, conditional and unconditional branches, function calls and returns, and endian conversions. memory areaThe ISA identifies five memory regions, each with well-defined boundaries (i.e., [addr, addr+len]), into which programs can read or write:

The program has a predefined virtual memory map, with the program code starting at address 0x000000000 or 0x100000000, depending on the compilation version, the stack frame starting at 0x200000000, the heap starting at 0x300000000, and the input data starting at 0x400000000. validatorThe validator performs static analysis before execution - it checks every possible code path without running the program - to ensure safety guarantees are provided at load time rather than at run time. This includes checking:

While validators are useful, they don't prevent developers from introducing unexpected behavior. That said, developers can still introduce use-after-free and buffer overflow bugs into Solana programs, for example. Panic conditionPanic conditions are a list of runtime error cases defined by the SVM ISA. These include:

ABIThe Application Binary Interface (ABI) is the format contract between Solana programs and the SVM. While the basic program anatomy section earlier demonstrated how this works in Rust (i.e., a process_instruction with three inputs), the ABI specifies how these inputs and outputs are represented in memory, ensuring that each validator can execute the program deterministically. At a high level, the ABI defines three things: entry point conventions, calling conventions and registers, and memory layout. Every Solana program _must_ expose an entry point function. The loader serializes program input into the VM's memory space in a canonical order: program ID, account array, and instruction data. The VM then passes pointers to these areas to the program's entry point. The first five registers (i.e., R1-R5) are reserved for entry point parameters, while the return register (i.e., R0) holds the program's exit code. An exit code of zero is considered a success, while a non-zero value is a failure that maps to a specific InstructionError. This ensures that all programs return status codes in a consistent manner. Additionally, parameters after the first five parameters are passed on the stack. R6-R9 follow the callee-saved convention, which means that functions must retain these values when using them. Accounts and data are serialized as byte slices into the VM's linear memory. The program must deserialize them into higher-level Rust types (eg, AccountInfo, Pubkey). The ABI enforces strict boundaries so no program can access memory outside its allocated area. Together, these rules make the ABI the "glue" that binds the high-level developer experience to the low-level ISA. It ensures that simple Rust function signatures compile to correct register usage, memory layout, and return codes so that each verifier interprets a given program in the exact same way every time. SyscallsISA is intentionally minimal, with no built-in accounts or status. Nor does it directly provide any higher-level functionality such as logging, hashing, or cross-program calls. Instead, system calls are exposed—special functions built into the VM that allow programs to interact with the outside world. These calls are often called syscalls. Syscalls can be thought of as APIs provided by the VM. Syscall exposes secure, standardized operations guaranteed to operate in a deterministic manner across all validators, rather than each program having to reimplement specific cryptographic primitives or account logic. Popular syscall categories include:

Syscalls are called using a special CALL_IMM instruction with a unique hash identifier. When a program calls a syscall, the sBPF VM is trapped in execution, looks up the hash in its syscall registry, and dispatches to the native implementation running in privileged runtime code. Syscalls execute outside of the sandbox and have access to runtime state, which is completely different from how regular function calls in your program are executed. Syscall follows the same ABI as a regular function, the first five parameters are passed in through registers R1 to R5, and the return value is in R0. Each syscall has a fixed compute unit cost, ensuring deterministic resource consumption. For example, all calls to the secp256k1_recover syscall consume 25,000 CU. Syscalls form a controlled security boundary because each syscall validates its input and checks for associated permissions before performing any privileged operations. For example, a cross-program invocation (CPI) syscall verifies that the caller has the appropriate permissions for the account being passed. Note that new syscalls can be added through function gates without modifying the ISA itself. This allows Solana to extend its VM functionality to include support for new cryptographic primitives while maintaining backward compatibility with existing programs. program binariesAt the end of compilation, all stages - from Rust source code to LLVM IR, to eBPF, to sBPF and its compliance with the SVM ISA - produce a single output: the program binary. This binary is what is actually deployed to Solana. ELFSolana programs are compiled into Executable and Linkable Format (ELF) files, a standard binary format used in Unix-like systems. The ELF format acts as a container that packages everything a VM needs to execute a given program while maintaining platform independence. ELF files usually contain the following sections:

Each ELF file also includes a header that describes the architecture, instruction width (i.e., 64 bits), endianness (i.e., little endian), and entry point address. Links and relocationsThe process of converting compiler output into a single executable ELF file involves one final component: the linker. The linker is responsible for combining multiple compiled code units into a cohesive binary. It also resolves any _symbol references_ (i.e., placeholders) that are not resolved by the compiler. For example,

This process of rewriting a symbol reference to a specific address or hashed syscall ID is called relocation. However, it's worth noting that relocation is very much an artifact of the way the tool was originally built, rather than a fundamental requirement. In fact, there are plans to remove relocations entirely in future versions of the toolchain to simplify the deployment process. This relocation step is necessary to ensure that the same ELF binary runs the same way on all validators because there are no absolute memory addresses or system-specific symbols embedded. Additionally, the bytecode that already contains these relocations is cached in memory, so all future executions depend on the updated bytecode without reprocessing the relocations. Once the linker generates a fully relocated ELF file, the program is ready for deployment. The end result is a binary file which is:

How to upload bytecode to SolanaOnce the Solana program is compiled and linked into a valid ELF file, the next step is to upload it to the blockchain so that validators can execute it. This process, called program deployment, involves multiple components working together: BPF loader, account model, bytecode validation, and state management. BPF loader programThe BPF loader is a native program that verifies, relocates, and marks ELF files as executable. Essentially, it manages the lifecycle of a deployed program - it handles instructions to initialize accounts, writes bytecode, deploys the program, and handles upgrades. Solana has gone through several iterations of the loader, each improving on the previous version:

Deployment Architecture: Account ModelCurrent account modelThe current loader uses a dual-account architecture to separate program logic from program data. This results in two accounts for a given program: the Program account and the ProgramData account. The Program account is a small account, approximately 36 bytes in size, that holds metadata and marks files as executable. It stores a reference to ProgramData via UpgradeableLoaderState::Program { programdata_address }. The ProgramData account is a larger account that stores the actual ELF bytecode as well as deployment metadata (eg, slots, upgrade permission addresses) via UpgradeableLoaderState::ProgramData. The separation of the two accounts enables in-place upgrades. That is, the Program account remains at the same address, while the ProgramData account's bytecode can be replaced. future account modelLoader V4 is designed to simplify the deployment process with a single-account model. The idea here is that the program account will store metadata and bytecode directly, without the need for a separate ProgramData account. It also provides developers with the option to store zstd compressed images to save on rental costs. How to deploy a Solana programThe deployment process involves uploading the compiled ELF binary and having the BPF loader validate, cache, and mark it as executable. Due to the deployment architecture outlined in the previous section, the process is slightly different between the upgradeable loader and V4. BPF loader upgradeableThe current deployment process using the upgradeable loader involves initializing a buffer account for staging ELF bytecode. The deployer sends the InitializeBuffer directive to the BPF loader to upgrade, which creates a new account owned by the loader and sets the account state to UpgradeableLoaderState::Buffer { authority_address }, recording the address authorized to write to the buffer. The compiled ELF binary is uploaded to the buffer in chunks using the Write { offset, bytes } directive. Each write instruction verifies that the signer matches the buffer's permissions, checks that the buffer is still mutable (i.e., has not been deployed), and writes bytes at the specified offset after the metadata header. Note that due to transaction size limitations, large programs require multiple Write instructions to upload the entire ELF file. Once the buffer contains the complete ELF, the deployer sends a DeployWithMaxDataLen { max_data_len } directive. This is the most complex step in the entire deployment process, as it coordinates the actual deployment from account verification to status completion. The loader first validates all accounts during deployment and verifies:

The loader then creates a ProgramData account, using the program ID and loader ID to derive the address for the PDA. It then queues the buffer's lamport back to the payer because the buffer account is no longer needed after deployment. Additionally, it creates a ProgramData account to the system program via CPI, allocating enough space for metadata and max_data_len bytes. The loader then uses the PDA's bump seed to sign the CPI. The deploy_program! macro ensures that the bytecode is safe to execute. It first parses the ELF file structure to verify ELF magic bytes (i.e., 0x7f 'E' 'L' 'F') and headers (i.e., 64-bit, little-endian), extracts program sections, processes relocation tables, and verifies section boundaries and alignment. If the ELF is malformed or uses unsupported functionality, the load will fail immediately. RequisiteVerifier (i.e., sBPF's verifier) then performs a static analysis of every possible execution path without running the program, ensuring that it is provably safe before executing any instructions. The validator also enforces the SVM ISA constraints mentioned earlier. If validation fails, deployment is rejected with InstructionError::InvalidAccountData and the program is never marked as executable. Once verified, the bytecode is compiled and cached for execution. The load_program_from_bytes function creates a ProgramCacheEntry containing:

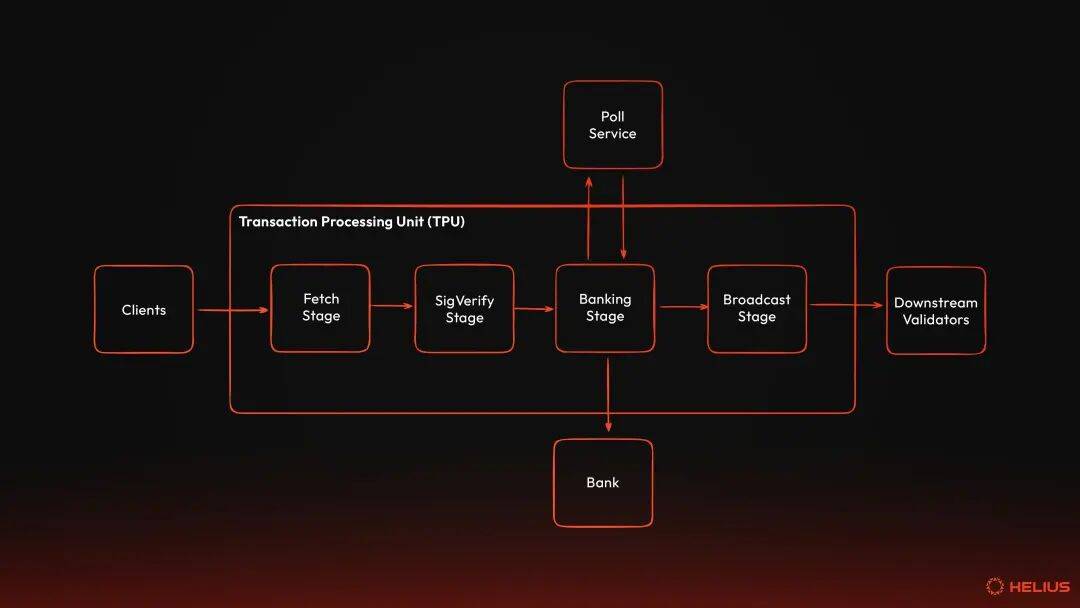

Cache entries are stored in program_cache_for_tx_batch, making the program available for execution on subsequent transactions. After successfully validating and caching the program, the loader updates the account status to complete the deployment. The status of the ProgramData account is updated to record when the program was deployed and who was authorized to upgrade the program. ELF bytecode is also copied from the buffer into the account. The Program account's status is also updated to link it to the ProgramData account and marked as executable. Finally, the buffer's data length is set to the metadata size, effectively zeroing out the bytecode and reclaiming space. The program is now fully deployed and can be called by transactions. BPF loader V4BPF Loader V4 simplifies deployment by eliminating the need for a separate ProgramData account, allowing program accounts to store bytecode directly. It also introduces support for zstd compressed ELF storage, which significantly reduces rental costs while decompressing on demand during loading. The deployer calls SetProgramLength { new_size } to allocate space for program metadata and bytecode. For new programs, this will initialize the account with the LoaderV4State::Retracted state, record permissions, and mark the account as executable, although it cannot yet be called. The deployer then writes the ELF binary directly to the program account via the Write { offset, bytes } directive. These writes are only allowed when the program is in the Retracted state. The Copy directive can also be used to copy bytecode from another program, regardless of loader version, which is useful for migrations. Then, use the Deploy directive to transition the program from the Retracted state to the Deployed state. Essentially, this instruction extracts the bytecode from an offset in the program account and runs the exact same verification pipeline as the BPF loader upgradeable (i.e. ELF parsing, static verification, JIT compilation, caching). If verification is successful, the program's status is updated to LoaderV4Status::Deployed, and the deployment slot is recorded. The program is now fully deployed and can be called by transactions. Loader V4 also enforces a cool-down period between state transitions (i.e., deploy and recall) to prevent redeployment attacks. The program cannot be deployed or recalled in a slot where it was last deployed. This helps prevent malicious actors from rapidly updating programs to exploit race conditions or confuse users, ensuring per-socket atomicity rather than multi-socket latency. Note that this cool-down period applies to Deploy and Retract directives. Programs can also be made immutable via the Finalize directive. This transitions the program from the Deployed state to the Finalized state, which means the program can no longer be rolled back or upgraded. The permissions field was repurposed to point to the "next version" program address, enabling an explicit upgrade path while maintaining program immutability. How execution works in SVMThe SVM is the transaction processing engine within the validator and is responsible for executing program calls and updating state accordingly. When a transaction reaches the validator, it flows through a multi-stage pipeline: validation, account loading, program execution in an isolated sBPF VM, immutability verification, and state commit. If all instructions are successful, the account changes are written to AccountsDB. If any instruction fails, the entire transaction is atomically rolled back. SVM operates as a decoupled execution engine. That is, it does not manage consensus, network, or ledger history. Instead, it focuses solely on executing programs safely, deterministically, and efficiently. The Bank coordinates the execution of the SVM, provides runtime context (e.g., block hashes, rents, feature sets), and commits the results to persistent storage. SVM manages program execution, from loading bytecode to enforcing compute budgets. This separation of concerns makes the SVM reusable outside of the validator. tradeTransactions are the lifeblood of Solana or any blockchain - they call programs to perform state changes. A transaction is a set of instructions outlining what actions should be performed, on which accounts, and whether they have the necessary permissions to perform those actions. Instructions are instructions called by a single program. It is the smallest execution logic unit and serves as the most basic operating unit on Solana. The program interprets the data passed in from the instructions to operate the specified account. Instructions include the program ID (i.e., the program to be called), a list of accounts to read from and write to, and the input passed to the program. A transaction begins when the user defines a goal, such as transferring 10 SOL to another account. This intent is translated into an instruction that tells the system program to transfer 10 SOL from Account A to Account B. Account A will be passed into the transaction as a writable signer, and Account B will be passed as a writable account. This instruction is then packaged into a transaction that also specifies the fee payer, signer, and the most recent block hash. The transaction is then typically sent to an RPC provider such as Helius. The RPC node receiving the transaction will then verify that all required signatures are present and valid, that the transaction has not yet been processed, that the most recent block hash provided is still valid, and that the transaction does not exceed the maximum size (i.e., 1232 bytes). RPC then forwards the transaction to the current leader's Transaction Processing Unit (TPU). Transaction Processing Unit (TPU) The Transaction Processing Unit (TPU) is the transaction ingestion and processing pipeline within the Solana validator. It has several stages that receive, verify, schedule, and execute transactions before they are submitted to Solana's ledger. For our purposes, we will examine the extraction phase, SigVerify phase, and banking phase in detail before proceeding with the configuration of the Bank and sBPF VMs. For a more detailed examination of TPU, see Equity-weighted service quality: everything you need to know。 Extraction stageThe extraction stage is the first stage in the TPU pipeline. It receives all incoming transactions over a QUIC connection, which utilizes UDP sockets as the underlying transport layer, and batches them for downstream processing. Three UDP sockets are created:

These sockets are registered with the validator's gossip service and stored in the ContactInfo structure, allowing other validators and RPC nodes to discover where to send transactions. The fetch phase spawns one thread per socket, all threads continuously:

Unbounded channels are currently used to pass batches to downstream stages, meaning the channel has unlimited capacity. The use of unbounded channels also means that the extraction stage can run independently of the downstream processing speed. While this prevents packets from being dropped immediately during traffic spikes, it can cause memory issues: if the downstream stage cannot keep up with the ingestion stage, the channel will grow at an unbounded rate, potentially causing slowdowns or out-of-memory (OOM) crashes. Efforts are underway to implement bounded channels with appropriate backpressure, allowing the system to signal congestion and prevent unbounded memory growth. The Fetch phase also creates a thread dedicated to forwarding packets. These packets are marked with FORWARDEDflag and are retained or dropped according to the leader schedule:

|